Rehabilitating Charity Hospital

2022

Charity Hospital’s closure disrupted a safety net of support for the public’s mental and physical well-being. The adaptive reuse of Charity into affordable housing with environmentally-informed building strategies aims to rehabilitate its legacy of improving the wellness of the surrounding community.

Approach

The legacy of Charity Hospital in New Orleans centers in public care, providing health care services to anyone regardless of economic status or insurance. It was the second oldest hospital in the country until its closure amidst the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Charity Over Time

Charity occupied five previous buildings before its current iteration, nicknamed “Big Charity,” which was built in 1938-39. Charity’s opening caused a ripple effect with the opening of other public hospitals in multiple cities in Louisiana including New Orleans.

Inverse Relationship between Prison and Hospitals

Inverse Relationship between Prison and HospitalsIn 1997, LSU took over hospital management. In July of 2005, LSU presented a plan to the state legislature to receive funding for a new private hospital, which the state denied. In August of 2005, Katrina made landfall. Though Charity experienced flooding in the basement, the building overall did not sustain considerable damage. Staff prepared the hospital to reopen after just a few weeks of repair and cleaning. Unfortunately, LSU had no plans to reopen and instead battled with FEMA to use Katrina as an opportunity to receive funding for the new private hospital, which they were eventually granted.

Loss of Hospitals & Housing

Loss of Hospitals & HousingCharity Hospital officially closed in September of 2005. Just as Charity prompted an opening of public hospitals in Louisiana, its closure prompted these same hospitals to shut their doors. Just as hospitals became privatized, mixed income housing replaced public housing developments Iberville and Faubourg Lafitte, displacing most original residents. Many identify this period of post-Katrina privatization as an example of disaster capitalism. LSU opened the new private facility in 2015. Ironically, after years of vacancy, Charity is currently in the process of redevelopment into mixed-use luxury housing and will likely never be used as a hospital again.

Privatization vs. Rehabilitation

When the safety net of public health clinics throughout the state disappeared, the protocol for caring for mentally ill people changed. The first response strategy is now, overwhelmingly, incarceration instead of treatment. With these rippling effects of Charity’s closure, the rehabilitation of the building necessitates socio-cultural thoughtfulness.The above graphic demonstrates how community access to affordable housing and healthy environmental conditions benefits many people, whereas privatization of space benefits few.

Rent as % Income & Surface Temperature

Overlaying surveys of high surface temperatures with concentrations of people paying more than 30% of their income on rent revealed a direct relationship between the two.

Axes of Social Engagement

To reconnect the hospital to the neighboring Duncan Plaza—a significant site for public protest, today and historically—the design carves a semi-covered exterior space in the quadrant of Charity’s site closest to the plaza. The axis of Duncan Plaza informs subtractions from the ground floor massing, connecting all plazas on the site and to pulling passersby from the street into them. Plantings also follow this grid.

Environmental & Social Connectivity

Given the overall unaffordable housing landscape and the effects of climate change in New Orleans, the continuing legacy of Charity would reasonably include the creation of housing for low income communities and workforce communities, as well as the implementation of urban environmental strategies that lead to community wellness.

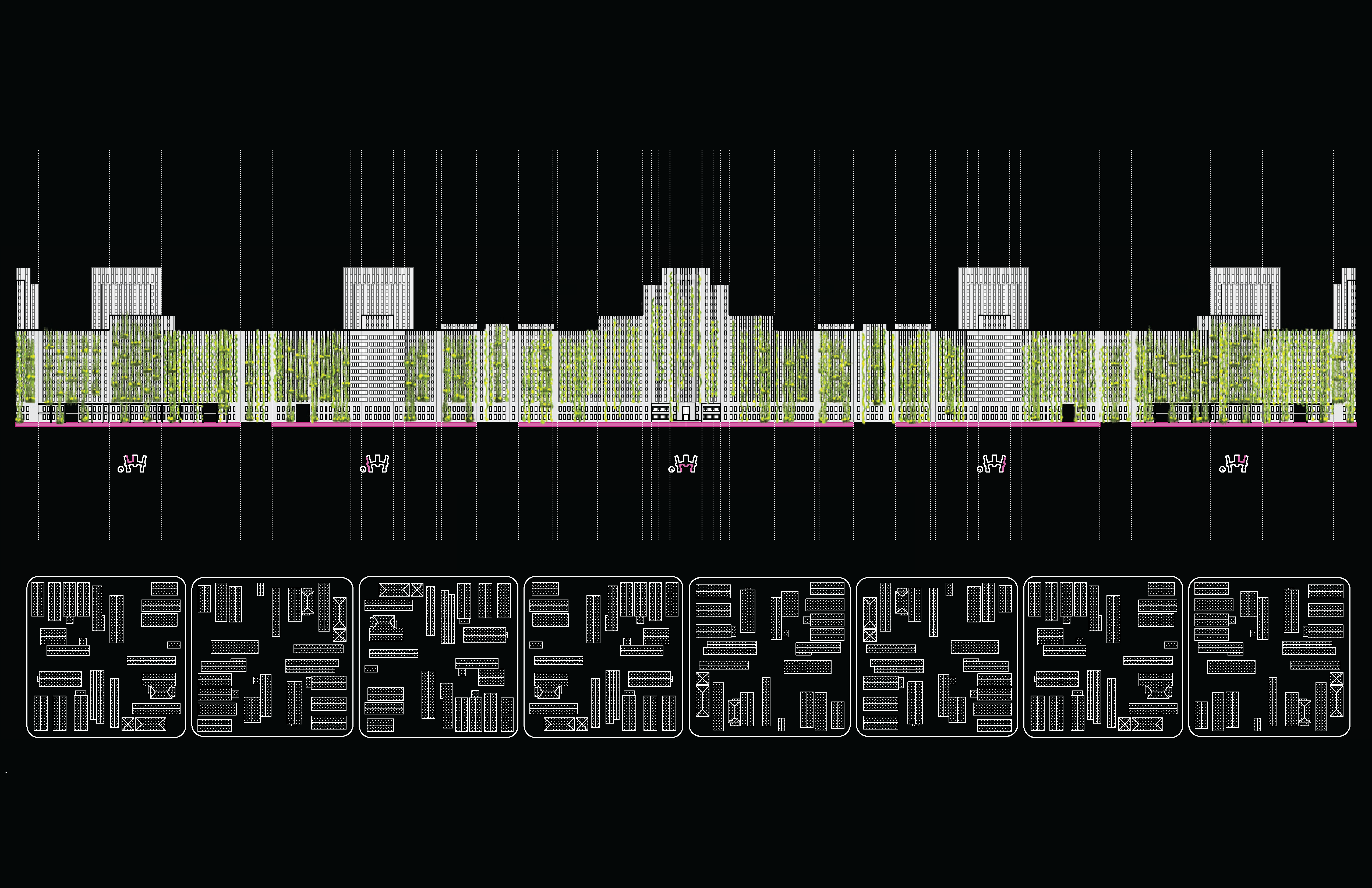

An initial exercise of unfolding the facade of the building demonstrates the overall effect of the facade as it exists currently, with the unfolded length equating to nine 300’ city blocks.

An initial exercise of unfolding the facade of the building demonstrates the overall effect of the facade as it exists currently, with the unfolded length equating to nine 300’ city blocks.

The placement of vegetation absorbs heat, improves air quality, and creates an adjacency to thriving ecosystems within an urban context for biophilic purposes.

The placement of vegetation absorbs heat, improves air quality, and creates an adjacency to thriving ecosystems within an urban context for biophilic purposes.

Existing vs. Proposed:

Outdoor Space, Vertical Cores, Circulation

Outdoor Space, Vertical Cores, Circulation

The structural components remain intact to aid a more economical and less materially wasteful result. The structural patterns, combined with the path of the sun, guided the design. Circulation adapted to allow for single-loaded conditions where possible to optimize cross-ventilation within units.

Public Atrium

A large atrium creates an indoor park for the public, including viewing mezzanines with hanging planters for the residents on upper floors. This space provides a natural threshold between public plazas and the private residential areas.

Unfolded Façade

Unfolded FaçadeThis unfolded elevation incorporates both of the facade strategies with more gradient conditions in the nooks of the building.

Cooling through Evapotranspiration

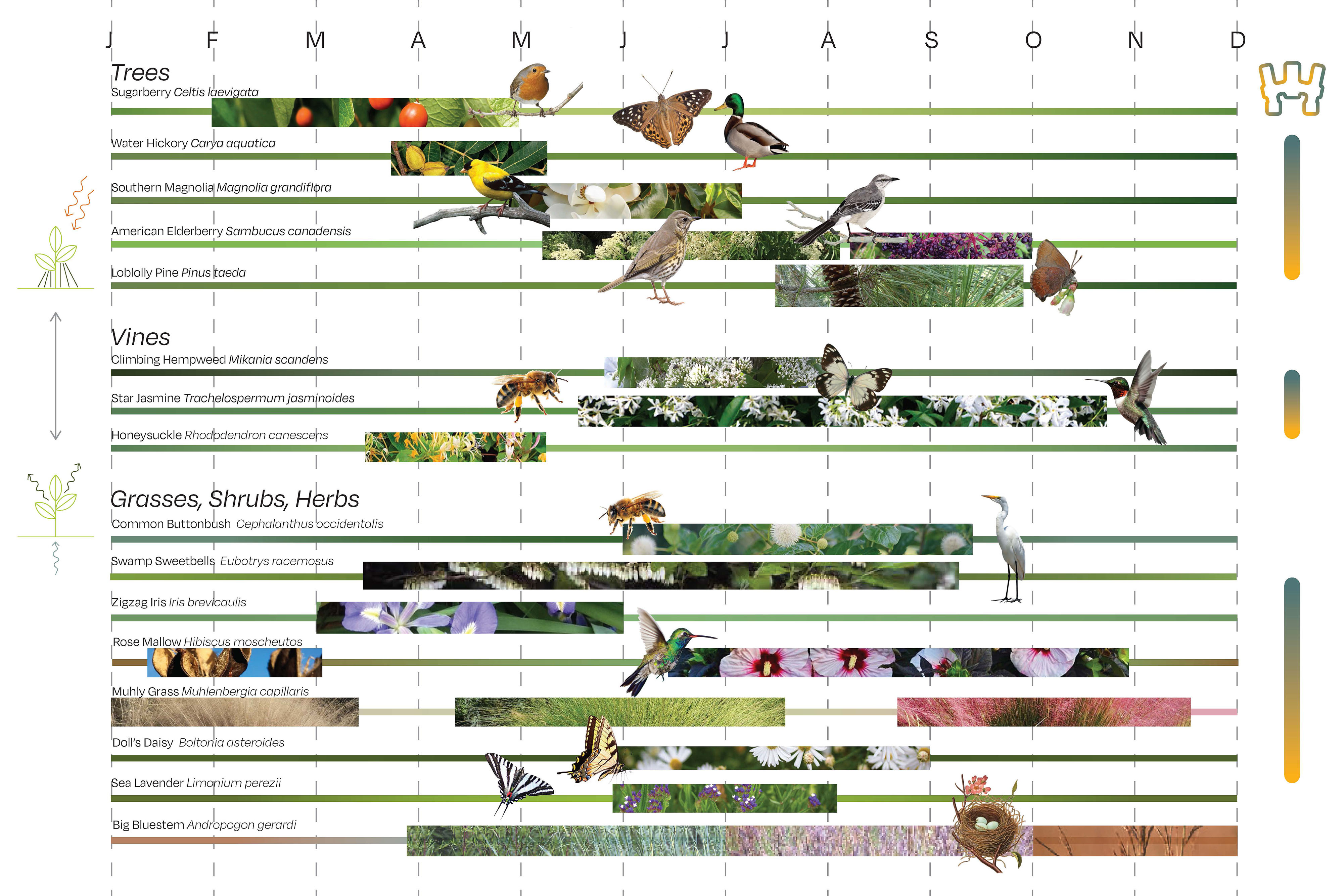

A selection of native plants offer both shade—cooling the surface area below the foliage—as well as evapotranspiration—diffusely cooling the air surrounding the plant. The most cooling-effective plantings are small and dense, as smaller leaves stay cooler for longer and dense vegetation creates more shading. Other factors for selection included maintenance requirements, native plant guidelines, seasonality, and productiveness towards surrounding ecosystems.

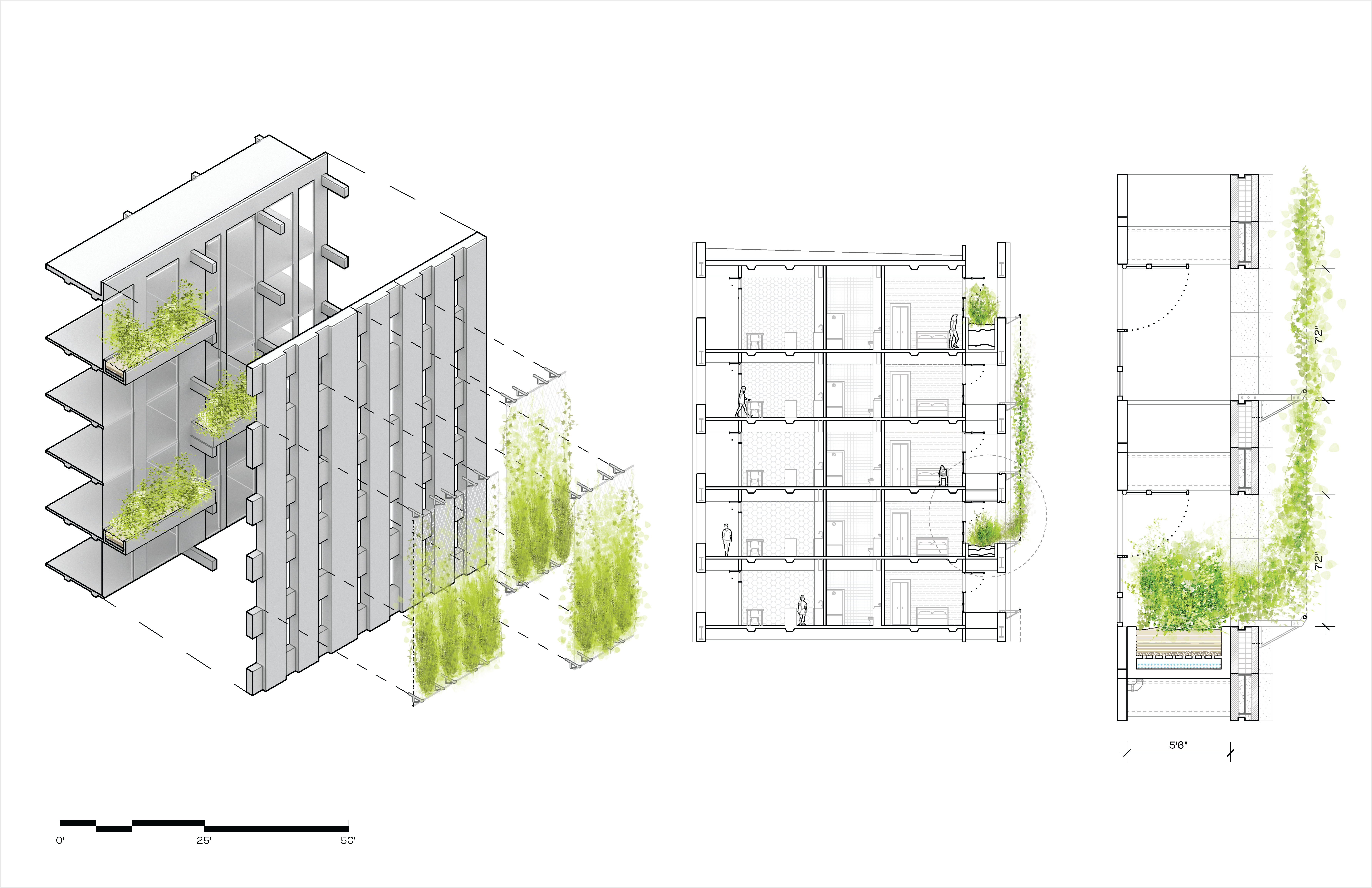

Façade Detailing

Façade DetailingAlternating vertically on every third floor, planter boxes sit inside the facade, as breeze over a moist soil substrate contributes significantly to cooling capabilities. Stainless steel net panels attach at the openings created by removing the existing window fenestration, preserving the appearance of the historic facade as much as possible.

Unit Layout & Aggregation

Superimposing the structural grid on a typical elevation determined a pattern of bay sizing. In order to make units more affordable, the larger bays are divided in half to provide micro-units and the naturally smaller bays contain a single unit with more bedrooms. In single-loaded corridors, the units push away from the facade to create the cooling cavity.

Cooling Cavity

Cooling CavityThe separation of the original facade from the exterior walls of the housing units creates a cavity for breeze over watered plants to cool the building. This condition also makes space for aviary wildlife habitation.

Ground Floor Plan

Programs such as an auditorium, an art gallery, and pools rest on the right side of this drawing, tucked between surrounding buildings and away from busy corridors. The center component allows for flex space for programming and resident events, while the leftmost portion of the plan includes small-scale markets and studios. Each vertical core is accompanied by a lobby space.

Typical Floor Plan

Cooling cavities follow the facades oriented to retain the most heat.

Public Plaza

A rehabilitated Charity Hospital could offer space to foster positive forces for the surrounding community facing challenges such as unaffordable housing and urban heat island effects. The cooling facade contributes to the mental wellness of residents and passersby, as well as contributes positively to the surrounding ecosystems.

Thank you to my research and design partner, Valentina Mancera, for collaborating ︎

Featured on Dezeen.

Featured on Dezeen.